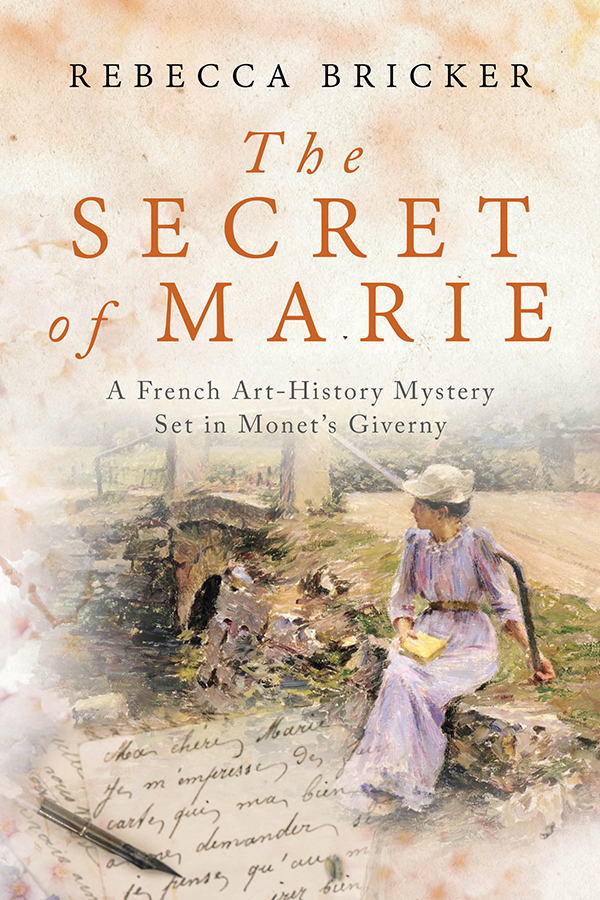

During the past few months, I’ve enjoyed sharing the story of The Secret of Marie as I’ve traveled across the U.S. on a book tour that took me from southern California to the Chicago suburbs to Evansville, Wisconsin, and finally to New Jersey and New York City. It was wonderful seeing old friends and making new ones along the way. I’m deeply grateful for the kindness, enthusiastic support and hospitality shown to me by so many during my travels.

The idea for this book came to me 12 years ago, during my first stay in Giverny, France, where Claude Monet spent the last half of his life. He immortalized his now-famous Giverny flower garden and lily pond in paintings that are treasured jewels of museum collections around the world. Today, more than 500,000 visitors come to see Monet’s house and gardens each year. I’ve been among them on my many visits to Giverny, as I immersed myself in the history of this bucolic village that was a flourishing artists’ colony at the turn of the last century.

The Secret of Marie was inspired by what happened to me on that visit in 2004, when I discovered the work of American Impressionist painter Theodore Robinson, who became a close friend and correspondent of Monet’s. As I learned more about Robinson, I became intrigued with his relationship with his favorite model, known only as Marie.

The Secret of Marie was inspired by what happened to me on that visit in 2004, when I discovered the work of American Impressionist painter Theodore Robinson, who became a close friend and correspondent of Monet’s. As I learned more about Robinson, I became intrigued with his relationship with his favorite model, known only as Marie.

Although I had read excerpts from Robinson’s diaries in the course of my research, it was a thrill to see four of his original journals at the Frick Library in New York City, during my visit there in May. He writes very little about Marie, which adds to the mystery of their relationship. It seems theirs was a tortured romance that came with a painful decision not to marry. But happily, their friendship endured. After Robinson last saw Marie in Paris, in 1892, he corresponded with her and, in fact, received a letter from her just a few months before he died in 1896, of a severe asthma attack at the tragically young age of 43.

A highlight of the book tour was my visit to Evansville, Wisconsin, where Robinson grew up. I had been in contact with local historian Ruth Ann Montgomery, whose Robinson research was considerable help to me in piecing together the timeline of his early life. She, in turn, introduced me to Kendall Schneider, also of Evansville, who is the president of the Theodore Robinson Society.

A highlight of the book tour was my visit to Evansville, Wisconsin, where Robinson grew up. I had been in contact with local historian Ruth Ann Montgomery, whose Robinson research was considerable help to me in piecing together the timeline of his early life. She, in turn, introduced me to Kendall Schneider, also of Evansville, who is the president of the Theodore Robinson Society.

Kendall was an extraordinary host during my visit, showing me Evansville’s historic sites, including the house where Robinson lived (right) and the school he attended. We visited the local cemetery, where Robinson is buried. Next to the family tombstone is an easel, placed there by the Society’s artists’ group, which holds a plein-air painting competition every year in Robinson’s honor. In Impressionist style, the artists render their work out in the “open air,” in the countryside surrounding Evansville.

My Evansville hostess Heidi Carvin, who kindly offered me her guest room, was in the midst of planning the installation of a labyrinth at a local park, next to a former seminary where Robinson had gone to school as a boy (his father had been a Methodist minister). She was collecting donations for the labyrinth’s pavers at the time of my visit, and I was only too happy to contribute. She asked her donors for a word or phrase that people could meditate on as they walked the labyrinth. I chose SERENDIPITY.

My Evansville hostess Heidi Carvin, who kindly offered me her guest room, was in the midst of planning the installation of a labyrinth at a local park, next to a former seminary where Robinson had gone to school as a boy (his father had been a Methodist minister). She was collecting donations for the labyrinth’s pavers at the time of my visit, and I was only too happy to contribute. She asked her donors for a word or phrase that people could meditate on as they walked the labyrinth. I chose SERENDIPITY.

Just my luck that Heidi is a master gardener. One of my hostess gifts to her was flower seeds from Monet’s garden to plant in her own garden. I’ve also asked her to plant some of those seeds at Theodore’s grave.

The ultimate end to this journey came serendipitously just a few weeks ago when I was in Giverny at the same time Kendall was in Paris. He and his lovely wife Debbie came to Giverny for a couple of days and stayed at Moulin des Chennevières, a featured location in the book.

The ultimate end to this journey came serendipitously just a few weeks ago when I was in Giverny at the same time Kendall was in Paris. He and his lovely wife Debbie came to Giverny for a couple of days and stayed at Moulin des Chennevières, a featured location in the book.

There was talk during Kendall’s visit of the possibility of Giverny and Evansville becoming sister cities. How wonderful that would be — a modern-day link between Monet and Robinson, one of the few American artists in Giverny whom Monet welcomed into his inner circle. I can imagine plein-air painters from Evansville coming to Giverny, following in Robinson’s footsteps, and painters from Giverny visiting Evansville, which is beautifully situated in the rolling farmland and woodlands of southern Wisconsin.

Before I left Giverny a few weeks ago, I had the delight of an off-road, four-wheel-drive tour by Jean-Pierre Guillemard, who was born in Giverny and has lived there much of his life. His family has lived in Giverny for four generations. (His youngest brother Gérard, along with Gérard’s wife Stéphanie, own the Moulin des Chennevières.) Jean-Pierre and Gérard’s grandmother knew Monet personally — he was her next-door neighbor.

Jean-Pierre drove me on barely passable tracks through hillsides surrounding the village where Impressionist artists painted more than a century ago. He took me to the meadow of wildflowers where Robinson likely painted Marie as she read a book, in an exquisite painting called Val d’Arconville, which I recently saw at the Art Institute of Chicago. And to end the tour, Jean-Pierre showed me a patch of poppies in a wheat field near the Seine. I almost expected to see Monet with his easel there. 🙂

Jean-Pierre drove me on barely passable tracks through hillsides surrounding the village where Impressionist artists painted more than a century ago. He took me to the meadow of wildflowers where Robinson likely painted Marie as she read a book, in an exquisite painting called Val d’Arconville, which I recently saw at the Art Institute of Chicago. And to end the tour, Jean-Pierre showed me a patch of poppies in a wheat field near the Seine. I almost expected to see Monet with his easel there. 🙂

This has been a wonderful journey that has come full circle. I feel blessed by serendipity and the kindness of friends and strangers. I’m especially grateful to the village of Giverny, to which I’ve dedicated my book, for so graciously welcoming me during my many visits there.

I’ve often wondered what Theodore Robinson would think of all this. An American woman telling his story and speculating about his romance with Marie. But I hope he wouldn’t mind too much. I’ve pleasantly sensed his presence at many turns as I’ve worked on this book.

One of the mysteries that presented during my research was the location of the Giverny garden where Robinson photographed Marie. The first known photo of her face is revealed on the last page of the book, as she stands next to a fruit tree with a bent limb, in a garden with a high stone wall.

On a suggestion from Giverny’s mayor Claude Landais whom I met this spring, I went to the far end of the village, past the church where Monet is buried, and walked up an incline that gave me a view of a garden hidden by a high stone wall. I walked down a lane to get another view of it, standing on my tip-toes. In the corner of the garden, there’s an old gnarled fruit tree, similar in its growth habit to the tree in the photo.

I looked up at the late afternoon sky and smiled. Theo, is this the place? Give me a sign.

As I walked away, I turned around to take one last look. And suddenly the forsythia behind the garden wall caught the sunlight. It lasted just a few minutes and then the sun dropped below the clouds.

I think it was a sign. 😉

Credit: book-signing photo — Dave Neesley

{ 11 comments }